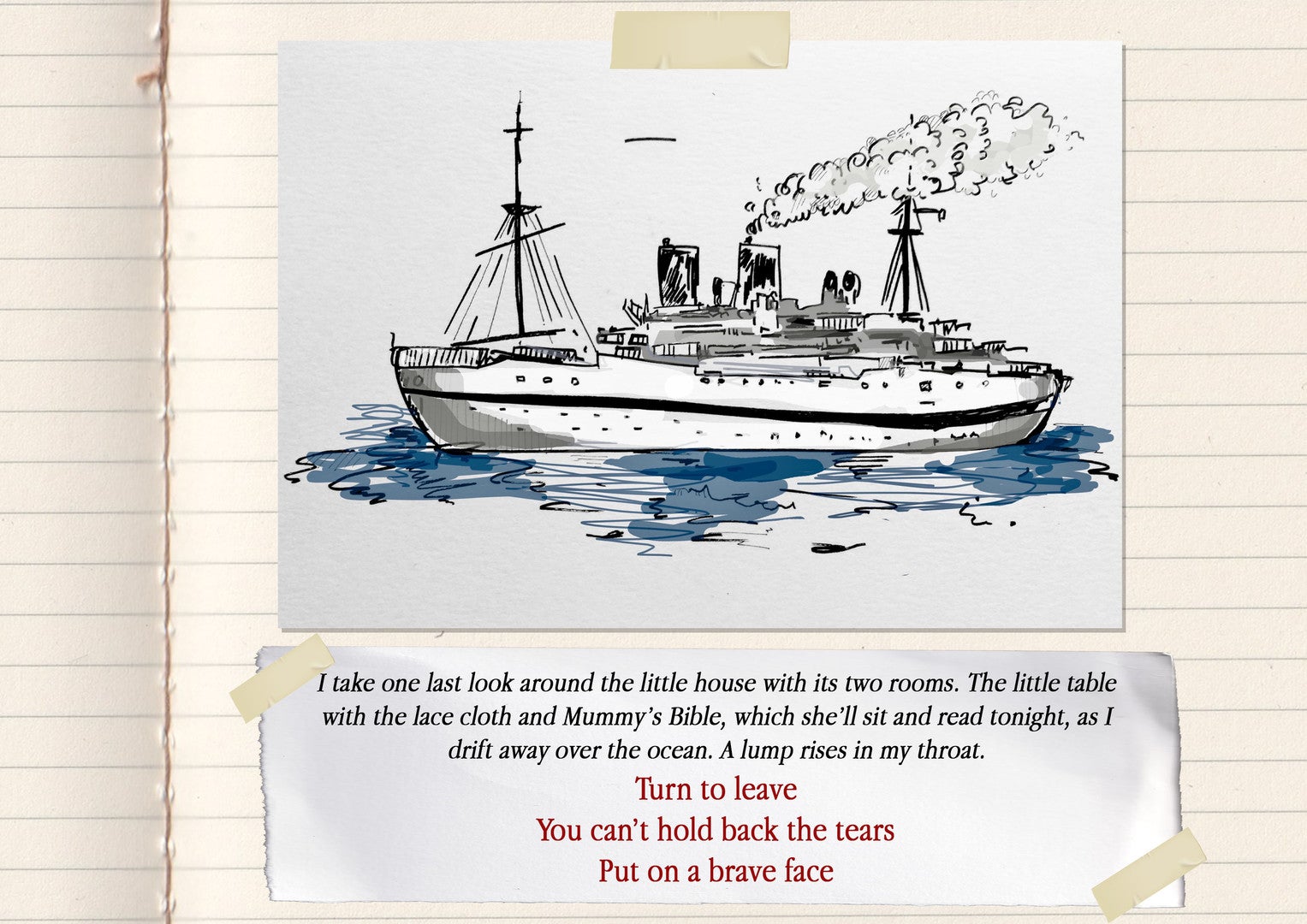

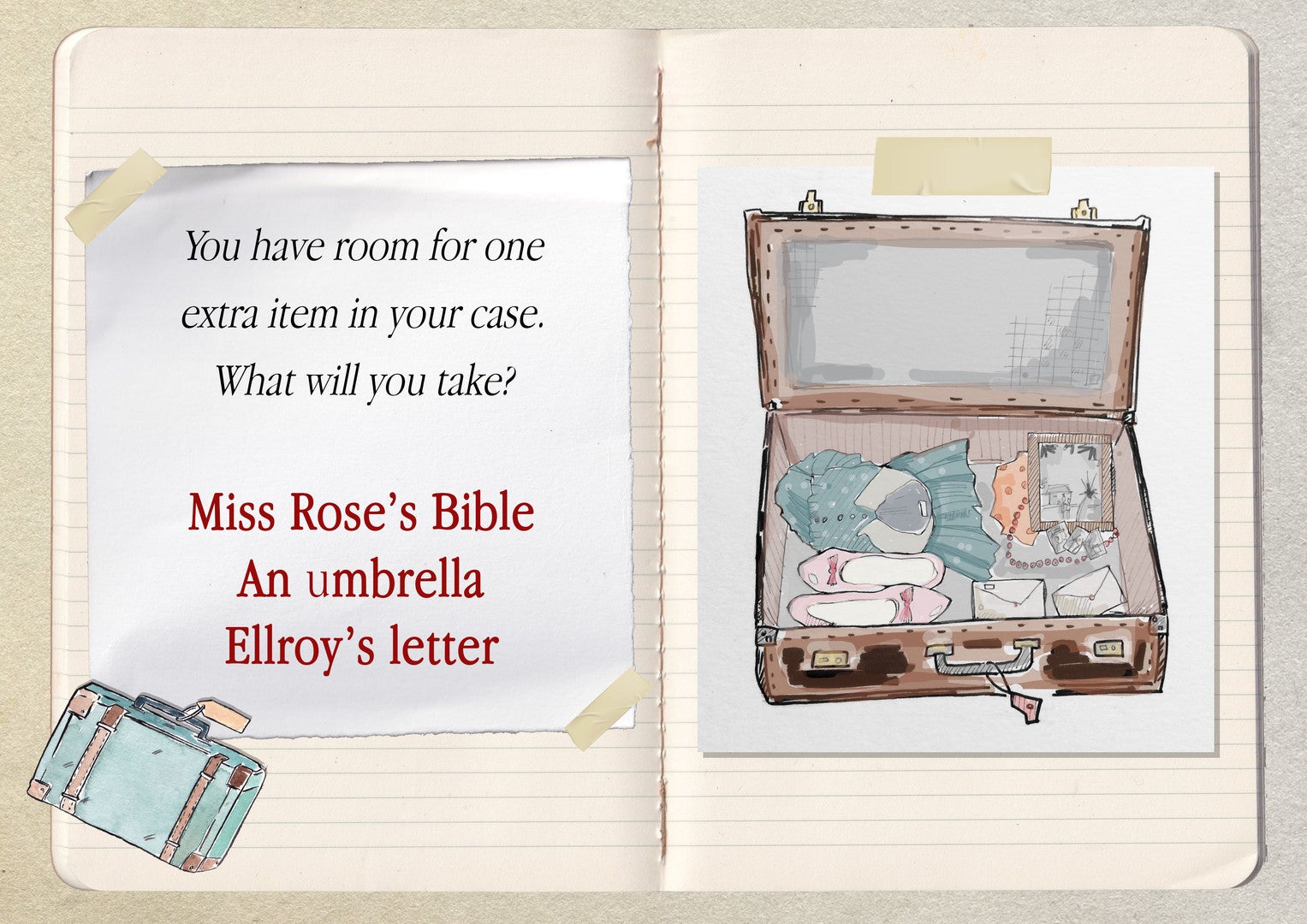

A lot is owed to those people - the people of the Windrush generation - who faced and overcame adversity to settle in the UK. They laid the foundations for a multiculturalism that we, the people who live here, gain so much from today. From food to music to fashion to sport: the impact has been immense. The Windrush’s arrival is such a significant part of modern British history it was even recreated for the opening ceremony of the London 2012 Olympic Games. This is why Chella Ramanan and Corey Brotherson, who both have Caribbean heritage, were planning to make a game to celebrate the 70th anniversary of Windrush. Chella Ramanan is the writer and narrative designer behind Before I Forget, a BAFTA-nominated game about a woman living with dementia; and Corey Brotherson is a writer of comics, screenplays and video games. He even briefly wrote for Eurogamer a very long time ago. Chella Ramanan’s father came to the UK from Grenada, a small island in the Caribbean, in the 1950s. She is, as she said during a GDC talk I watched earlier this year, “a child of Windrush”, and she wanted to celebrate the cultural impact the Windrush generation has had. “There is no representation of Caribbean people in games, really, especially the British Caribbean experience,” she said during that talk. “People don’t know it beyond the UK.” So, she wanted to change that. Corey Brotherson’s grandfather came to the UK from St Kitts in 1955. He left his wife and children behind to try and establish a life in the UK they could eventually join. “And his experiences vary,” Brotherson says. “It wasn’t like he had horrendous experiences here. He had a couple of bad moments, and naturally it was very lonely and isolating for him at times, but for the most part it was good enough for him to feel like it’s fine for my grandmother and my dad and all of his siblings to come over, which I’m obviously very grateful for.” Brotherson’s grandfather, now in his 90s, recorded his experiences here in a leaflet - or a “very, very small novella” - in the early noughties. And it’s exactly this kind of experience Ramanan and Brotherson wanted to draw on as the inspiration for their game. Their idea was to follow people leaving the Caribbean for a new life in the UK, and to show it from their point of view. “We wanted to tell a story that faced the hardships,” Ramanan says, “but led us, ultimately, to this point where Corey and I are in this country, and we’re British, and we feel British and Caribbean, and all the wonderful impact that our community has had on the UK.” And they would end it with Carnival, which is to say the Notting Hill Carnival: an annual celebration created in response to violent discrimination, and which now stands as one of the world’s largest carnival events. They chose Carnival because this game was supposed to be uplifting. It was supposed to be optimistic. That’s how they felt at the time. “There was this wave of feeling as a black person that was like, ‘Oh, we’re being more heard, we’re being more seen. There’s more elements of our culture being pushed out into popular culture, through films and through TV series,’” Brotherson says. But, this was in 2017, and the entire situation was about to change. As the year rolled on and into 2018, reports began to emerge of people from the Windrush generation being put in dire situations by the state. They were losing jobs and facing eviction from their homes. They were issued NHS medical bills, despite having paid taxes for decades. In more extreme cases, they faced detention and deportation. And it was all because they were being asked to provide paperwork that either didn’t exist, or had disappeared a long time ago. This hunger for paperwork came from what Theresa May, the then Home Secretary of the UK, coined as a “hostile environment” for illegal migrants when announcing it in 2012. It would push landlords and employers and the NHS to be stricter about getting paperwork from their tenants or employees or patients. She endorsed it as a way of getting tough on people living here without permission, whereas in reality, she ended up punishing tens of thousands of people living here with permission. Many of the Windrush generation had come into the UK on parents’ passports so didn’t have paperwork of their own. The Home Office had also destroyed thousands of landing cards and other records from the time, eradicating proof people now needed. Also, we’re talking about hundreds of thousands of people and decades of time having passed. Imagine being asked to provide an official document for every year you’d lived in the UK when you’d been here 20, 30, or even more years. The Guardian reported that around 50,000 people found themselves in trouble because of it, and it’s reported that 83 people were wrongly deported because of it. It’s a situation that would go on to be referred to as a scandal, the Windrush scandal, and lead to governmental resignations, scathing investigations, apologies and even promises of compensation. But the compensation is taking too long to get to people, and deportations are still happening. It is far from over. This crushed the optimism they held onto in their game. “There was just an overwhelming sort of rage and sadness and disappointment,” Ramanan says. “A feeling of betrayal,” she adds, with emotion in her voice. “What made it worse was there was all this talk about Brexit at that period of time, too,” Brotherson says, “and this level of xenophobia and I guess bigotry that’s growing from that. […] I didn’t have many family or family friends that were directly affected, thankfully, because they came so relatively late during that generation that they had a lot of their documents, or they reached a point where it wasn’t so much of an issue. But there was still that sense of concern and feeling, that sense of ostracisation again, that sense of being pushed out, which is a horrible thing to consider when you’ve been in this country for so long, and were in many respects told to [go] back to what was deemed as your home. “And having all of that suddenly just in a concentrated dose: it was very difficult to escape that feeling of negativity and anger that was around at that period of time, from everything that happened. […] It’s quite a jolt of cold water to throw on your hopes of being able to be accepted.” It upended plans for their game. The tagline had once been “a game of hope” but couldn’t be any longer. When they met up to talk about it, they knew it would have to change. “I remember us both being quite downcast and just like,” Brotherson sighs, “‘Jesus.’” They didn’t completely abandon the idea but the tone had to change. They couldn’t really end with Carnival any more, Ramanan says with a wry laugh. And it meant that while they’d always intended to face the hardships of being black in an overwhelmingly white Britain in the 50s and 60s, one in which shop windows had signs declaring ’no blacks’, now they would have to explore racism “a lot more than we would have”. They would add gameplay elements that would highlight it - that would, as Ramanan says, “somehow reflect that experience of navigating a society that largely doesn’t want you”. And that’s more or less where they are today. Windrush Tales is still in pre-production so the team can’t say too much about what it will be. I do know, though, it will follow three characters coming from the Caribbean to the UK, each with different motivations and goals, and different ideas about what an ideal life in Britain should look like, and have different ways of getting it. “Hopefully that’ll give a nice rounded view of the experience in itself,” Brotherson says, “but also explore things which may not have necessarily been explored in other media when it comes to talking about Windrush. “One of the things that Chella has always wanted to stress - and it touches upon what Chella was saying earlier on in terms of not being disingenuous to the experience of that generation - [is] to not create ‘struggle, the game’. It’s not just about the hardship and dealing with microaggressions, and dealing with all the issues and challenges that come with being in the UK during the 50s and the 60s as a black person. We want to be able to express and explore the culture as well, and the celebration of that. And also the wins; ultimately, that’s what it comes down to. This is a generation that, for most of the part, stuck it out despite all the hardships that were there.” Windrush Tales will play like you’re reading a journal, from what I understand - a kind of storybook experience where you’re flicking through scrap books of photos and notes and drawings and diary entries to build a picture of a life. And it sounds like you’ll interact with them in some way too, perhaps choosing what the character will do in certain moments. You can already get a glimpse at what it will look like on the Windrush Tales Steam page, and in a few pictures in this piece. What you’re seeing is the hand drawn artwork of Chella Rmanan’s niece, Naima Ramanan, who’s also on the team. Rounding out the quartet is Claire Morwood, co-developer of Before I Forget, and co-founder of her and Chella Ramanan’s studio, 3-Fold Games, and she’s a general creative collaborator on the game. This is not, however, a 3-Fold Games’ game. It is a 3-Fold Presents game, which is a brand new label created by 3-Fold to allow them to collaborate with other people and serve as a kind of umbrella brand for doing that. Windrush Tales was initially Chella Ramanan’s side project, so it’s effectively a collaboration that Claire Morwood joined later on. It’s a way of working they’ve always wanted. Windrush Tales still has a fair way to go. Exactly how long, I don’t know because they wouldn’t say, though they have an internal timeline in mind, but they’re still in pre-production, and they’re still looking for arts funding to top up their own investment in the game. But the potential is strong, judging by Before I Forget. And it’s another powerful reminder that games can help us examine important topics, too. They are mature and capable enough now. And in the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter protests and the calls to re-examine the British history that schools teach, few subjects seem more powerfully relevant than this one. “What do we want people to learn about Windrush?” Ramanan says, mulling the question. I’m sure there’s much she’d like to say. But this is not a lecture. At its heart, I think it’s still a celebration. “I think really this game is for those people who are part of the Caribbean community and have relatives who are part of Windrush,” she says, “to see their story as a video game.” To see their experiences reflected, their perseverance, their joy, their life. “And that’s really empowering and vital and validating.”